Over the years the process of figuring out if the idea will work and become financially stable was an extremely expensive and time-consuming experience.

In our fourth stage of the Clinical Innovation Fellowships program 2021, we went about to discover how to prototype our idea and how to make a valid business model.

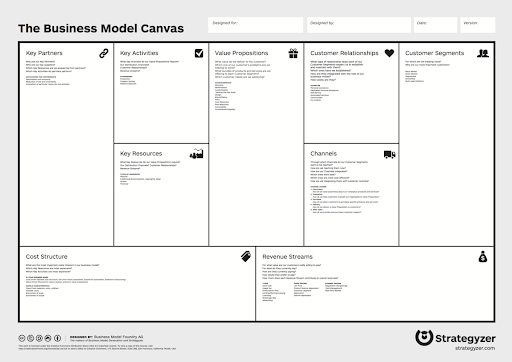

Let’s first dive into the Business Model Canvas!

Business Model Canvas is one of the most famous and reliable tools for entrepreneurs transforming their ideas into actionable plans.

The tool enables the entrepreneurs a clear idea about every aspect of their business, starting from the target segment, value proposition, operations to finance. Its efficiency is related to its simplicity; presented as nine simple boxes for each segment.

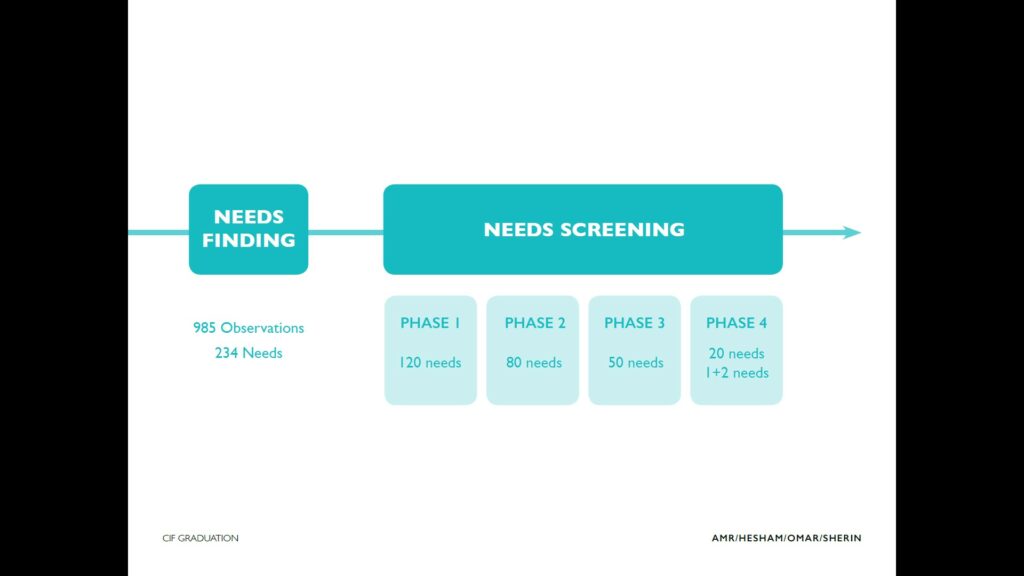

What really happened in this stage took us about a month and a half. We started with a clear objective: enhancing the blood supply chain in Egypt, putting our main need statement ahead: “A way to improve the efficiency of hospitals to find needed blood products to avoid the delay and cancelation of procedures.”

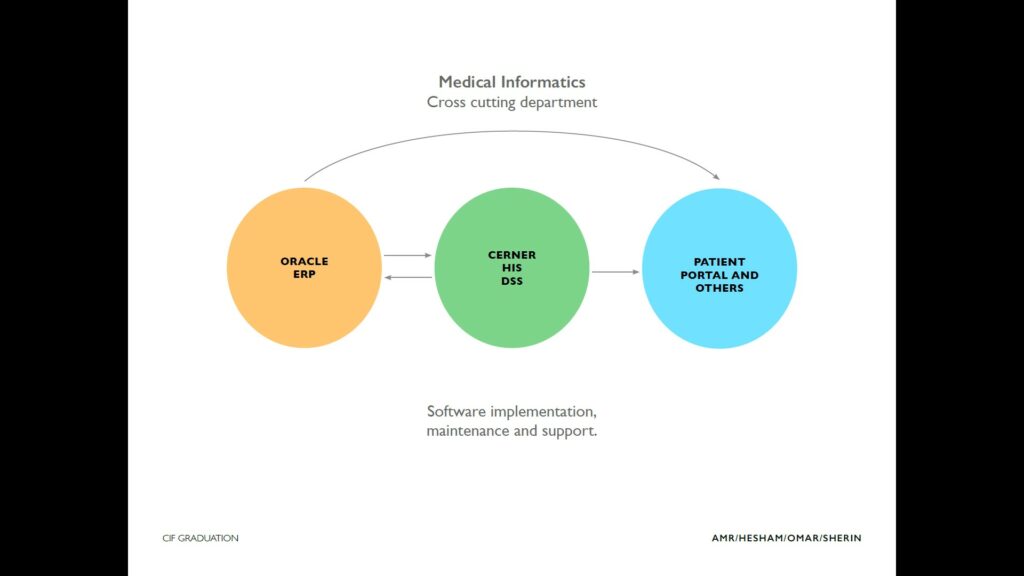

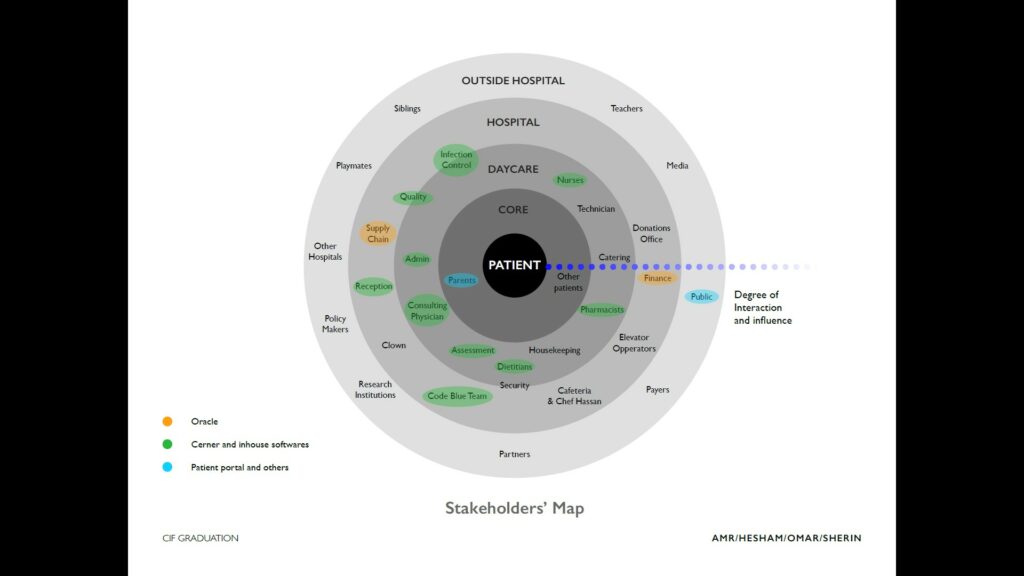

We started by analyzing the main stakeholders, including public, private, and non-profit hospitals, then we identified three assets:

- Stakeholders Map

- Stakeholders Persona

- User Journey for each stakeholder; what are their pain points, opportunities, and actions

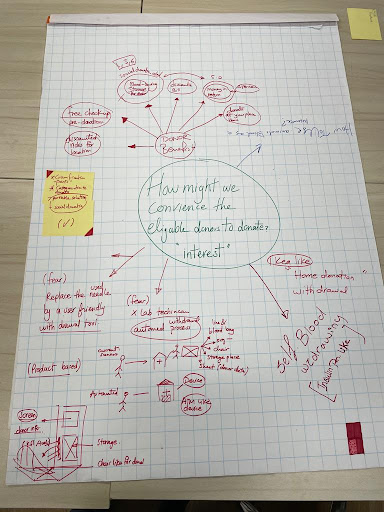

In order to identify the problem further, we made an insightful exercise called Service Blueprint. It is a diagram that visualizes the relationships between different service components: people, props (physical or digital evidence), and processes — that are directly tied to touchpoints in a specific customer journey. This exercise made us understand the problem more clearly and grasp the main touchpoints that we should focus on.

Afterward, our next steps took us to research the globally existing solutions for improving blood supply chains. We explored how the problem is being tackled and recognized our prospecting competitors in the field.

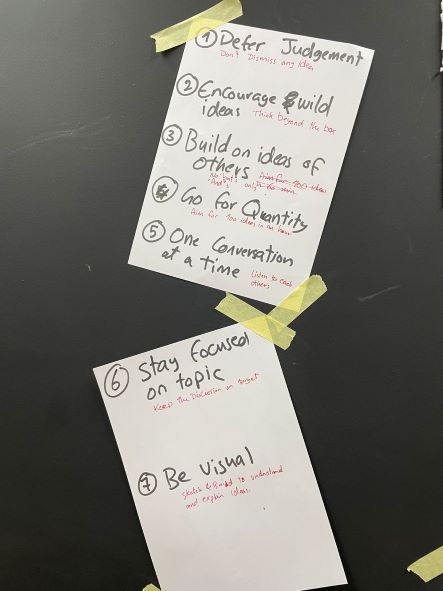

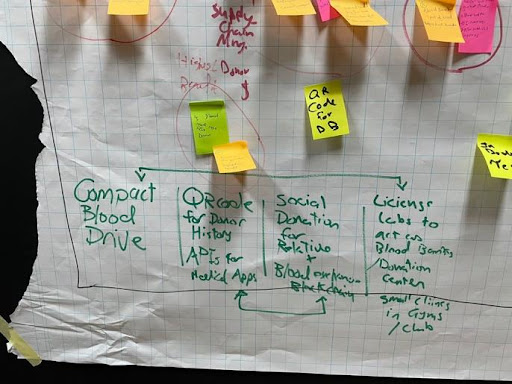

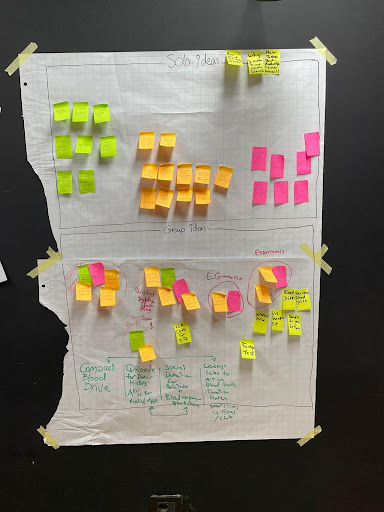

A brainstorming session was also helpful for us to utilize the knowledge we reached into a practical solution. Ultimately, we settled on the solution that we as a team believe it can resolve the problem.

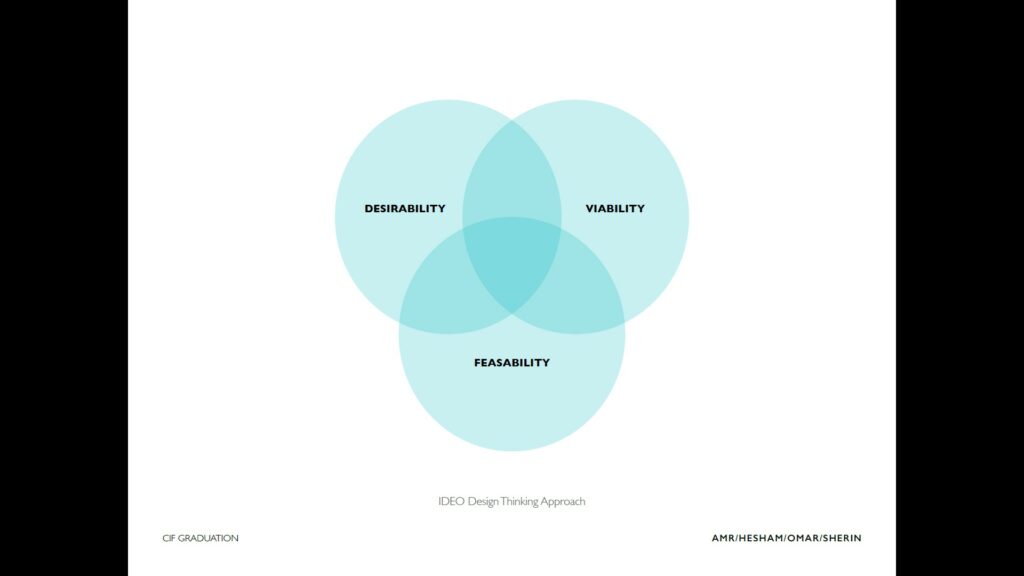

We made a prototype and a structured roadmap to measure and validate our idea; The roadmap we put comprised the following:

· Technical feasibility

· Competition

· Unique value proposition

· Customer feedback

And here was a new phase! We reached out to all the stakeholders we interviewed during our primary research to present our solution and get their feedback. What we encountered was a bit surprising as the market is absolutely competitive. After those interviews, we took a step back to discuss as a team if we will do the pivot.

With the support of our mentor Ahmed Yosry, we reached that we need to focus on one stakeholder that the problem impacts the most, and it was the private hospital sector. This sector can benefit from our solution supplying it with a specific yet rare blood type. From there, we can then have a roadmap to connect the other stakeholders to the solution later on.

We put the prototype and reached private blood banks with our solution. The first verbal deal we got was with one renowned private hospital. We also started a short-termed campaign to validate the interest of the donor. The results were optimistic! We received responses from the rare blood type donors who were ready to donate. So, we put a new roadmap to mark our milestones and see what we need to do to reach them.

This was a key moment for us! Our idea is valid and it can work!

In the end, I want to say it was a fruitful journey for me, with its ups and downs, I learned a lot, in a few months, how the public health sector works; That could have taken years for me to learn on my own, thanks to the educational resources that the program provided through its respectful base of experienced mentors – We can’t be more grateful to them for supporting us in every stage over the course of the program.

The Clinical Innovation Fellowships Program was a life-changing experience for me!

Mahmoud Tohamy, Clinical Innovation Fellow 2021